Women have successfully invaded the male sanctuary whose door men are least likely to unlatch for them: the world of baseball.

Men passionate about baseball, especially about the history of the national game, have for thirty-eight years participated in the international group called the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR), a group that stands at the top of the heap for solid, dependable baseball information. Fans come to conferences and conventions of this 6,500-member international group to hobnob with baseball authors, hear presentations disclosing the results of the latest scholarly research on baseball, and wallow in the authors’ books and articles.

Now, increasingly, those baseball authors are women. At a SABR meeting called the Seymour Conference, held in Cleveland April 27-29, 2007, three of the seven scholarly speakers who held the fifty-person audience spellbound were not men but women. I was one of them, and my remarks opened with the disclaimer, “We women are not consciously trying to take over this conference!” But maybe we are. Wouldn’t it be ironic if the oracle of this bastion of male hegemony ended up being a woman?

The Seymour Medal

Some women fans always attend each Seymour Conference, an annual gathering that focuses on a literary award. But others aren’t fans.

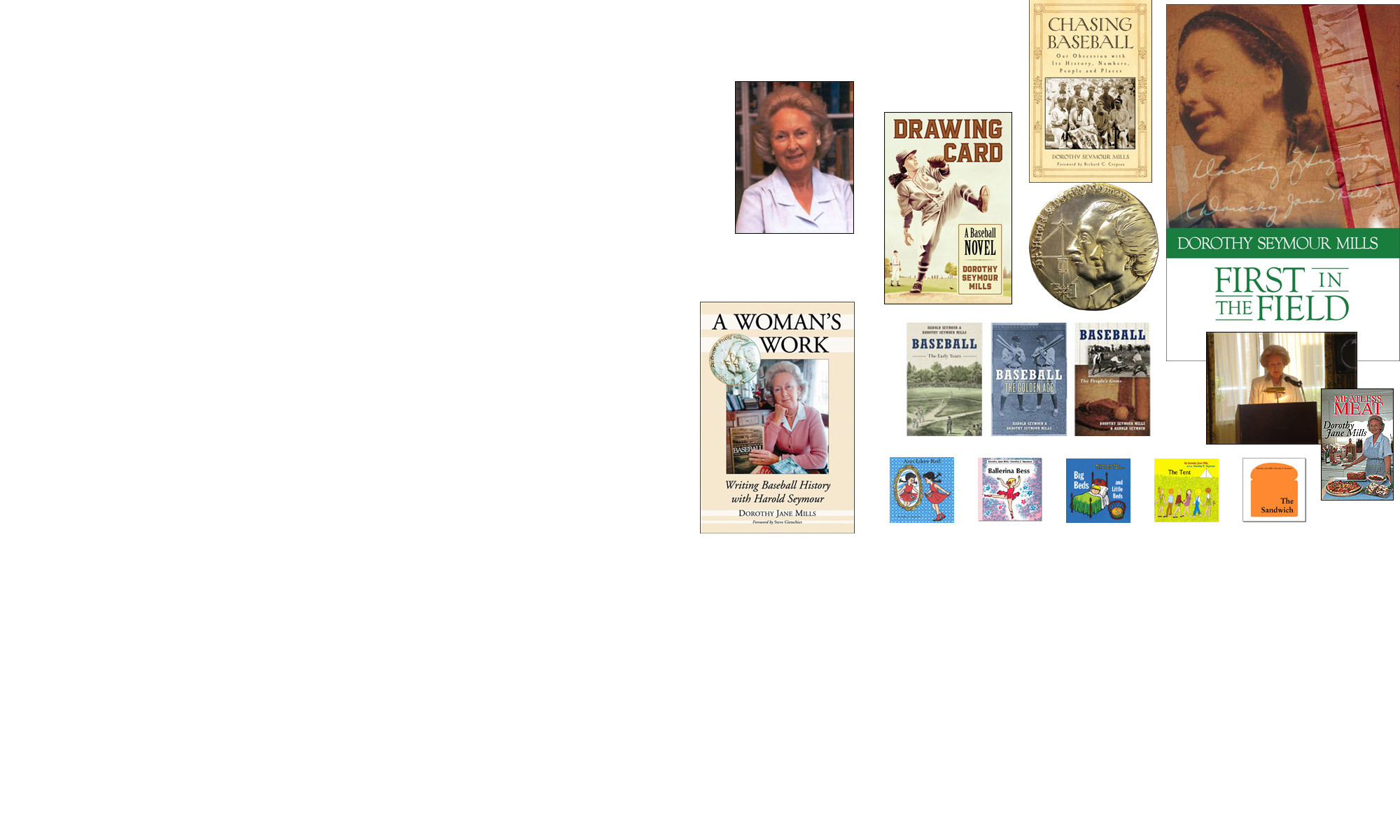

They are scholars competing with men for the top prize in the field: a heavy bronze medal awarded to the author of the best book of baseball history or biography published in the previous year. The medal is named for my late husband, Dr. Harold Seymour, and me.

Although no woman has yet won the award for having independently written a fine baseball book of history or biography, three have already been shortlisted for the award.

The first Seymour Medal was presented to me, in 1996, in belated recognition of the fact that I was secretly my late husband’s co-author and researcher for the trilogy that comprised the first scholarly books ever written in this field.

In 2007, for the third time in SABR’s history, a woman’s book made it as a runner-up for the Medal. Fittingly, the woman who almost won the top honor wrote her book about a uniquely feminine undertaking in baseball history: the All-American Girls’ Professional Baseball League of the 1940s, made famous by Penny Marshall’s film, “A League of Their Own.”

The history of the AAGPBL was written by Merrie Fidler, a retired teacher and coach as well as lifelong baseball enthusiast. Her book disclosing the origin and exciting story of this unique league is based on her thesis for the master’s degree at the University of Massachusetts, so you know it’s solid history. Merrie, who also keeps in close contact with the retired women professional ball players and has been elected to their board, was in attendance at the 2007 Seymour Conference (she brought her mom along, too) in order to enjoy the distinction of being one of the women to make it to the finals for this coveted award.

Merrie and all other SABR members are now fully aware that Dr. Seymour was the first scholar ever to pursue the research and writing of baseball history and that as his co-author I was the first woman in this field. Not until after his death in 1992, however, did I emerge from my Trojan horse and reveal my role in helping to produce the three-volume history of baseball published by Oxford University Press under Harold Seymour’s name.

Reactions To My Role

I could almost feel the waves of surprise (and maybe dismay) rippling through the membership in the nineties as other scholars and fans reacted to the news that Harold Seymour, considered a spectacular researcher, didn’t produce all that ground-breaking work on his own but instead had steady lifelong help. But SABR recovered quickly, rising to the occasion by specifying that its newly-created Seymour Medal would display not only Harold Seymour’s name and profile but mine as well.

One long-time friend of Seymour’s who grew up with him in Brooklyn never recovered from the news, declaring in a letter to me that in writing about my experience I had “dishonored the memory of a great man.” By telling the truth? By revealing that men are sometimes unable to recognize and credit women’s accomplishments appropriately?

The world of publishing responded to my revelation very differently from the way Seymour’s lifelong pal did. McFarland, a publishing company that now produces many scholarly books on baseball, saw my accomplishment as a publishing opportunity. Emphasizing to me that I was “a pioneer of sorts, the first woman to spend years researching and writing baseball books,” the company’s acquisitions editor, Gary Mitchem, suggested that I write my autobiography and signed me to a contract. In 2004 McFarland published A Woman’s Work, a book in which I revealed the extent of my writing and research for the Seymour books during fifty years of my life and explaining how I fit my independent writing into that endeavor.

Since then, women writers have increasingly joined male authors in producing excellent books about the sport so closely linked with men that, until relatively recently, women were thought unable to handle it in any way-not playing the game at a high level, not officiating as umpires, not handling front office work, and certainly not writing baseball history or biography.

Women at a Baseball Conference

So who are these women who have jolted the establishment by joining the ranks of baseball specialists? Let’s start with those who spoke at SABR’s Seymour Conference in 2007. Besides me (Merrie Fidler, although present, didn’t make a formal presentation), the speakers were Monica Nucciarone, a college instructor, and Cait Murphy, an assistant managing editor at Fortune Magazine in New York. No weak and wimpish nobodies here.

Monica, for example, a vivacious young scholar (her email address begins curveballgirl), reported research that will change the baseball history books. Trekking across the mainland and studying records in Hawaii, she pursued the traces of Alexander Cartwright, long thought to be a rule-maker for the early style of play used by the New York Knickerbockers of the 1840s. In the process, Monica discovered that the evidence for Cartwright’s contribution to baseball is merely secondary and mainly oral, with nothing to back it in primary sources contemporaneous with Cartwright’s life.

This young woman has thus cast serious doubt on Cartwright’s assumed position as “father of the game” and proved that others on his team might just as easily have formulated the rules the Knickerbockers played under. By knocking the supports from under the assertions of earlier scholars, Monica has played the role of gutsy young iconoclast.

Who would have thought it from a woman? And she already has a book contract to publish her research and conclusions. As for Cait Murphy, here is another youthful contributor to a field that seldom sees a skirt. Cait’s book represents a study of one eventful year in major-league baseball, 1908, during which so many unexpected and even preposterous events occurred that the resulting book is entitled Crazy ’08, with the subtitle How a Cult of Cranks, Rogues, Boneheads, and Magnates Created the Greatest Year in Baseball History.

Cait’s book shows us that the year in baseball abounded with crooks, psychopaths, villains, politicians, prostitutes, inept players, star performers, embarrassing losses, and wonderful plays. She names the 1908 season the greatest in baseball history, and after reading her book, we know why. Appropriately for a SABR member who holds a degree in American Studies from Amherst, she states this conclusion on the basis not of opinions but of solid historical facts.

Producing Baseball History

But we need not stick to the events of the Spring Seymour Conference in order to show that women are now producing baseball history at the very top level. Consider Jean Hastings Ardell, a college teacher and writer from California as well as a frequent lecturer on women’s contributions to baseball. Her provocative book, Breaking into Baseball: Women and the National Pastime (Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), holds the distinction of being the second book by a woman ever to reach the finals for the Seymour Medal. Appropriately for its recognition by SABR, Jean’s book proves beyond a doubt, and with countless examples, that women have long been involved in every aspect of the game and in ways previously ignored.

Breaking into Baseball covers, for example, the contribution of women as amateur and professional players (there were many), fans (and you know how devoted many women are), umpires (you should meet a few of today’s!), club owners and executives (more than you thought), women in the media (it was tough for them at first), even “baseball annies” (she shows their effect on players). Jean writes so well that Steve Gietschier of The Sporting News calls her “a major league writer,” and as for her research, Marvin Miller of the Major League Players’ Association points out that she has uncovered “a mostly hidden trove of information.” Jean’s book is a solid work of history, and she graciously dedicates it to her husband Dan, a former first baseman for the Los Angeles Angels.

A book that is in some ways a companion to Breaking into Baseball is atrailblazing new work called Encyclopedia of Women and Baseball, published by McFarland in 2006. You didn’t think there were enough women in the entire history of baseball for an encyclopedia? Guess again. This 430-page tome contains hundreds of entries, including individual players, managers, teams, leagues, and topics, all dated from mid-nineteenth century onward into the present. The Encyclopedia includes several appendices, including rosters, tournament results, a 55-page bibliography, a listing of contributors, and a ten-page index. So your grandma played baseball for an independent team in 1930? You could look her up. If she’s not listed, let the editor know, for the next edition.

The person mainly responsible for producing this comprehensive work is a slight young woman named Leslie Heaphy, who is a history professor at Kent State University. Leslie has already published a history of the Negro Leagues that became the first woman’s book ever to reach the finals for the Seymour Medal. She earned this recognition in 2003. That book is based on her doctoral dissertation, so its scholarship can’t be faulted.

In preparing the Encyclopedia, Leslie solicited contributions from many who are knowledgeable about women’s baseball, nearly half of them women. Those contributors include Justine Siegal, president and founder of the Women’s Baseball League, which opened in 1997 and is still going strong.

Justine, a quiet but determined young blonde ballplayer and organizer, runs one of the strongest women’s leagues in North America, although others operate too. (Her tiny daughter, Jasmine, plans to play some day.) You thought women played only softball? The women of these baseball leagues have long scorned that game as too easy. Women baseball historians don’t confine their work to the study of other women in baseball. They publish biographies of males, too, and at SABR’s 2006 convention in Seattle a major presentation came from a statuesque brunette named Judith Testa, a retired art historian who is still actively writing. Testa has produced a fully-developed biography of Sal Maglie so good that Gabe Schechter of the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown commented, “I wish there were more baseball biographies where the author has done justice to the subject the way Testa has done full justice to Sal Maglie.” Author Donald Honig went further, declaring that “Testa’s book transcends its genre and is a first-rate work of literature.”

Judith Testa explains “baseball’s demon barber” as affected by his personal disappointments as well as his appearance, personality, and background. William Marshall, an author and professor of history, points out admiringly that “Few baseball biographies have dared to discuss the sexual or psychological aspects of players’ marriages in the manner this work does.” Women seem to me perfectly positioned to delve into the personal dimension of players’ lives and the way it affects their play. Judith’s book thus presents a fully rounded portrait of a fascinating person. That’s what good biography is all about.

Women at Baseball Conferences

Testa is just an example. Women are increasingly involved in SABR’s annual conventions, which are held in various North American cities and attract around 500 attendees. At the 2006 convention in Seattle, where Judith made her impressive presentation, a young woman named Allison Binns, a doctoral student in sociology at Harvard, won the award for best poster presentation, beating out both men and other women. Her poster graphically showed how she figured out which players performed better the season after undergoing salary arbitration, those who won their case or those who lost.

Women come to SABR conventions both to speak and to listen. Of the 539 members in attendance at the Seattle convention, 73 were women. That’s 13.5 percent of the people there, although women represent only 3.75 percent of the current SABR membership.

At that convention one of the speakers was Susan Dellinger, granddaughter of a Hall of Fame player. She described “the joys of biographical research” undertaken for her book, Red Legs and Black Sox: Edd Roush and the Untold Story of the 1919 World Series. Merrie Fidler made a presentation, too, about a hardly-known Latin American tour of some of the AAGPBL women in 1949.

So women are active in SABR out of all proportion to their membership figures. People noticed in Seattle that women were helping fill the hotel’s presentation rooms, addressing members at the podiums, crowding the halls, and chatting up authors as much as men were. Yet The New York Times, in its story covering the event, never mentioned women’s strong showing-just as the media in general omits to inform the public about events in current women’s baseball leagues.

SABR membership records show that although women currently make up 3.75 percent of the paid members, seven years ago they represented only 2.7 percent, so they have been joining at a good rate. Not only are women joining, they are participating in planning and organizing. They have formed their own Women’s Committee to operate on a level with SABR’s seven other standing committees.

The Women’s Committee emerged in 1990 at the suggestion of a clinical psychologist named Sharon Roepke, who also helped alumni of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League of the forties and fifties to reconnect and hold reunions. Sharon began this effort because after visiting the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1976, she realized that as far as the Hall was concerned, women players “were considerably more invisible than the Negro Leagues.” So she worked to get them the Hall of Fame recognition they now enjoy.

In 1995, Leslie Heaphy, the Seymour Medal finalist, who includes a course in baseball history among the classes she teaches at Kent State, took over the Women’s Committee of SABR and, with the cooperation of other SABR women, started publishing three women’s newsletters annually. It’s been shown that women colleagues keep in touch; these women certainly do.

A Woman at the Top

Something even more unexpected happened to the overwhelmingly male Society for American Baseball Research in the summer of 2001: a woman became president. And she’s a black woman.

Claudia Perry, who used to write a newspaper column about pop music (her email address opens with rockdog), ran for, and was elected to, the presidency of SABR, handling the job for the usual two-year term, although she didn’t seek re-election. Now a features general-assignment reporter for a Newark newspaper, Claudia, who is so sharp that she became a four-time champion on the national quiz program “Jeopardy” (she bought a house with her winnings), couldn’t appear at the panel in St. Louis in 2007 because of a scheduled knee operation. She said that she “would dearly love to be there,” for the reason that the Women’s Committee was planning something really special.

A Women’s Panel

At SABR’s Seattle Convention in 2006, the Women’s Committee offered a panel discussion that attracted some attention but wasn’t even listed in the program’s section on panels. That experience inspired the women to aim higher.

All the previous winter, with emails shooting back and forth across the country, and with the cooperation of Steve Gietschier of The Sporting News (he headed the St. Louis committee), SABR women plotted something big for the 37th SABR convention July 26-29: a full-blown panel on women in baseball, with the intriguing title, “Our Mothers’ Game (and Ours): Tales from the Women’s Side of Baseball.” Standout SABR women took part, and many others graced the audience.

At the top of the lineup was Jean Ardell, the California writer and lecturer. Jean moderated the panel’s discussions. Her delicious wit and pointed insights have entertained those attending past Women’s Committee meetings. She introduced the participants and led the panel in showing how baseball is truly “our mothers’ game (and ours).” Each participant told stories, many of them inspiring roars of laughter, and answered questions posed by the men who made up most of the audience of about 300 rapt listeners.

Judith Testa, the author of the striking new biography of Sal Maglie, told a little of what it was like to plunge into this new field after years of more academic writing about Italian Renaissance art-which she hasn’t given up. Having grown up with New York baseball, Judith has always thought of the game as existing on the periphery of her life. Now, with the publication of an entirely different kind of book, baseball has moved toward the center of her attention. She recounted to gales of laughs Hank Greenberg’s attempt to buy Maglie for Cleveland at a bargain-basement price.

Another participant was a young woman named Cecilia Tan, who is at the same time a baseball author, blogger, masseuse, and (probably more important) baseball player in the adult division of an important women’s league, the Pawtucket Slaterettes. Cecilia comes from what she calls a “Yankee-obsessed family.” She acts as senior writer for Gotham Baseball magazine; she also writes and edits an online magazine called Why I Like Baseball.

Do you get the idea that Cecilia is devoted to baseball all the way through to the tips of her long hair? She once declared that describing many of the pieces in the Cooperstown Hall of Fame as “memorabilia” is like describing New York City as a municipality. Cecilia explained how to start a women’s league and surprised the audience by urging others to start their own leagues.

One of the most significant questions asked of the panel was why women stopped playing baseball in college and amateur leagues back in the twenties and thirties, instead moving to softball. Cecilia Tan and I explained that it was the female college athletic directors, influenced by physicians (then almost all men), who had come to believe that women were not strong enough to play the game they had been playing for decades. The athletic directors eliminated college sponsorship of baseball and saw to it that only softball would be sponsored. The AAU then supported this decision, and it is only now that their rule is being challenged by the many women who want to play baseball, not softball.

Anyone remember Erma Bergmann? An outstanding Michigan pitcher in the famous AAGPBL of the 1940s, Erma played with the Springfield Sallies, the Racine Belles, the Battle Creek Belles, and the pennant-winning Muskegon Lassies. Once “Bergie,” as she was known, threw a no-hitter. The St. Louis Cardinals have twice recognized her achievements, and this year she was inducted into the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame. After her career as a baseball player she became one of St. Louis’s pioneer women policemen. When Erma compared her experience in the AAGPBL with the way the league was portrayed in “A League of Their Own,” she made an instant hit with the audience by commenting, “I never had a manager as drunk as Tom Hanks.”

And now for the front office. Here we brought up Melody Yount, who answers fans’ questions at Busch Stadium as Assistant Director of Media Relations for the St. Louis Cardinals. Phone her when you want to know anything at all about the team-yes, even its history. Did you ever imagine that a woman could handle such a position? Well, imagine it. Melody told the admiring audience what it feels like for a young woman who loves baseball to be hired to represent a major-league team to the public.

Sara Blasingame came to the panel viewing baseball from a different angle. As the daughter of major-leaguer Walker Cooper and the widow of major-leaguer Don Blasingame, she gave us the lowdown on what it’s like to see baseball from the inside. She revealed her love for the game despite the difficulties travel entailed, explaining her difficulty of shopping for clothes for her tall children in Japan, where her husband was playing at the time.

As for me, I rounded out the panel as the earliest woman researcher and writer in the field: the senior gal, in other words, mentoring others and savoring the delicious details of their fresh new contributions. I explained how baseball grew among upper-class college women of the 1870s as well as women in prison in the 19 teens. At Jean Ardell’s request, I also told a story from my autobiography, A Woman’s Work, about the amazed looks on the faces of the writers in the all-male Sporting News office when in 1949 in walked into to do research wearing the usual travel costume of the day: traveling suit, heels, hat, and gloves. I’m sure I was the first female to enter that room, for I caused cigars to drop from mouths, eyes to bug out of faces, and coffee to spill on desks.

The audience response to this session proved outstanding, and participants heard remarks like “you women really know your stuff!” and “that was simply fascinating!” and “that was the best session I’ve ever attended at any SABR convention.”

This panel also helped many of us sell our books. Judith Testa signed and sold all the copies of the Sal Maglie bio that her published had shipped to the convention, and my editor sold every copy of A Woman’s Work that he had brought. Of the thirty authors scheduled to autograph books at the Authors’ Table in the Vendors’ Room, six were women.

SABR women also took part in the general convention by making formal presentations to the entire membership. In St. Louis, Cait Murphy, the Fortune editor, presented an address called “Myths of the Early Deadball Era.” And as part of the annual competition for best historical poster, Cait prepared a display called “Cover-up: Gambling, Corruption, and the Wild Finish for the 1908 Season.” Catherine Groom Petroski made a nostalgic presentation on the life of her grandfather, the excellent pitcher Bob Groom, and showed some fine old photos. Jean Ardell, moderator of the women’s panel, also made a presentation to the membership with Roberta Newman, who teaches Cultural Foundation courses at New York University. Jean and Roberta jointly presented an address called “Women in the Stands: An Examination of the Commissioner’s Initiative on Women and Baseball of 2000 and Its Aftermath.” They told us how the clubs measured up to the Commissioner’s requirements.

Okay, so the SABR Convention of 2007 featured Joe Garagiola as luncheon speaker; that’s all right with us. We women can put up against him such heavy hitters as Ardell, Newman, Testa, and Yount. Sounds like an important legal firm. Just be thankful, fellows, that we don’t plan to start any lawsuits requesting compensation for all the years that some men insultingly assumed we weren’t capable of what we’re doing now.

As we relish what we are accomplishing, we can contemplate another important discovery about women in baseball. For on top of it all is the recent revelation by researcher David Block that baseball’s origins are very likely feminine.

David’s 2005 book for the University of Nebraska Press, Baseball Before We Knew It, details his exhaustive research both here and abroad into the origins of the game. And now David tells me he has learned that in England, where baseball was first played in the eighteenth century, it was a girls’ game at least as much as it was for boys and maybe even earlier than it was for boys.

So perhaps as women in baseball we are simply reclaiming our history. “Our Mothers’ Game” indeed!