“Women and baseball” is an aspect of baseball history that is becoming recognized. The Schlesinger Library of Radcliffe College in Harvard University owns a copy of my autobiography, A Woman’s Work, the librarian there tells me. Some scholars consider this book a feminist document. The Smith College library has a copy of Chasing Baseball for use in courses on sport history. Did you know sport history is taught in women’s colleges? Smith has also just discovered that I devoted two pages to early Smith baseball in Baseball: The People’s Game, the third volume of the series I wrote for Oxford University Press with Dr. Harold Seymour.

Women of the 1860s who found the courage to play baseball in long skirts, and women of the 2000s who realized that their gender has a history in baseball that is worth researching and writing about, deserve this kind of recognition.

The Women in Baseball Committee of the Society for American Baseball Research is a lively group that meets each summer during the SABR convention. At these meetings we discover the research that each woman is pursuing or the promotion of women’s baseball that she is engaged in. I look forward each summer to the stimulation that such meetings inspire. In between, many of us keep in touch via email to learn how projects are progressing. This summer, at the meeting in Philadelphia, I’ll have to report that my eBook for young people on the history of women’s baseball still isn’t finished, but I’m working on it regularly (in between producing book reviews and giving speeches), and eventually it will be available through Thinker Media.

Not all women historians write women’s history, however. Judith Testa wrote an admired biography of pitcher Sal Maglie. And Lynn Sutter has just released her biography of early player Arlie Latham. Women scholars do not feel bound to pursue any particular aspect of baseball history. They can take on any topic that calls to them, just as the male scholars do.

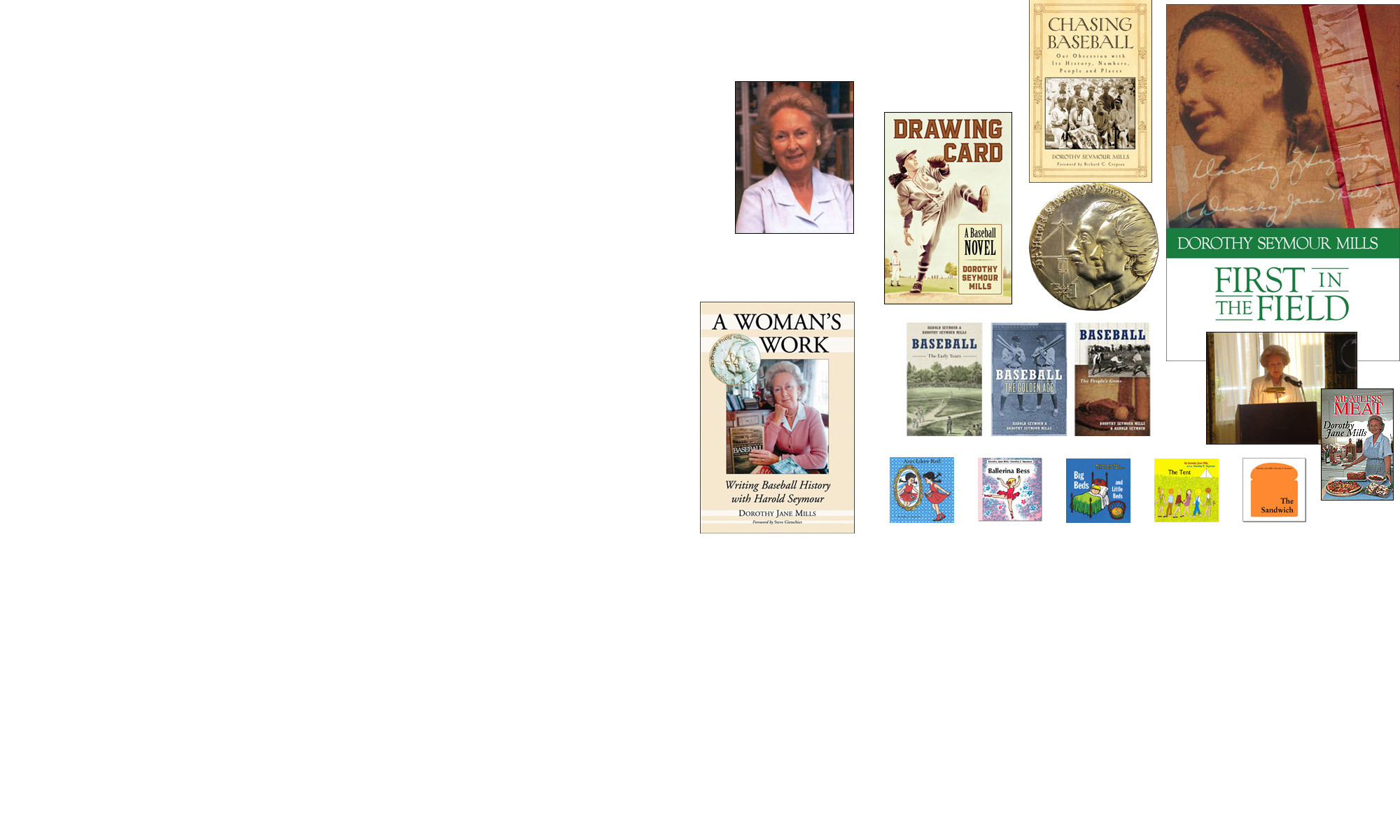

Women baseball historians have taken their places in the broad array of scholars studying our national game. I am proud to have been in on the ground floor of this movement. When I speak about my books, I like to display a little sign with a quotation from Jim Gates, Librarian of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York, on March 21, 2012: “Today, with dozens of graduate students of both genders laboring away at baseball-related dissertations, they can all thank Dorothy Seymour Mills for her efforts as a researcher and writer for making baseball history an accepted field of study.”

Women scholars have become accepted as contributors to the solid work being done in this “accepted field of study.”