In a scholarly paper read at the Spring Training Conference of NINE at Tempe, Ariz., this month, I heard a scholar read a carefully annotated paper about “Female Masculinity” as it is exemplified in a novel called Rachel, the Rabbi’s Wife, by Silvia Tennenbaum (Morrow 1978).

In his paper the scholar, a man from Ball State University named Adi Angel, asserted that in this novel the heroine uses her love of baseball to free herself from a male-dominated world, that “baseball serves as a vehicle for Rachel to seek liberation from her marriage,” and that Rachel “displays traits of female masculinity” with her “skills as a ballplayer.” He states that Rachel evinces a “desire to continue playing baseball while transitioning into adulthood,” that her “identity is tied to her desire to play the game,” and that she is a “character exhibiting masculine traits,” one whose “feeling of loss” at being unable to continue playing the game as a grownup “follows Rachel into adulthood.”

Having read a great deal of the history of real girls and women who have played baseball in childhood and youth, including those who are playing now, I was surprised at Angel’s interpretation of girls’ baseball play as masculine. So I read Tennenbaum’s novel. From this reading I came away with an entirely different view of the character of Rachel, the rabbi’s wife, and her experience with baseball, than the one described by Angel.

Rachel is an artist married to a rabbi who serves a middle-class congregation on Long Island. She lacks interest in the activities of the women members, especially their organization, the Sisterhood, which a rabbi’s wife is supposed to embrace, and prefers to work at her art, hoping to become, at least in a small way, a commercial success. At one point in the novel Rachel recalls a moment when during childhood on a playground, when playing softball (not baseball) with the neighborhood kids, a boy inadvertently touches her in a way that stimulates her sexually, and she realizes that she is becoming a woman.

At no time does the author of Rachel, the Rabbi’s Wife, indicate the heroine is at all skilled as a ballplayer or that she wants to continue playing baseball into adulthood. Although Angel has described her in his scholarly paper as a “tomboy,” neither the author nor the character herself indicates that in playing softball with the boys she sees herself as at all boyish.

The cultural construct known as “tomboy” has been used broadly to describe girls who enjoy active games as much as boys do. These girls do not state that they are engaging in masculine behavior; nor do they inevitably grow up to look or act masculine. The best example is the girls of the All-American Girls’ Baseball League of the 1940s and 1950s, who overwhelmingly looked and acted womanly; most of them eventually married men, and they produced a lot of babies. Interviews with these women elicited their reasons for playing as, for example, “to get away from home and travel,” “to make money as a ball player,” “to enjoy playing baseball every day,” and “to compete with other women players.” While playing ball a lot of them attracted male admirers, whom they dated while on the road, sometimes eluding their female chaperones to do so. None of this sounds like masculine behavior. That’s because baseball is not inherently a masculine game. One does not need masculine traits to play it. If a player needed to be masculine, women would not have been able to play it for 150 years, as they have done.

Nor does Rachel attempt to continue her youthful playground ball into adulthood. She never says, for example, “I miss playing softball.” Instead, she becomes a fan, one who keeps up with her favorite team and players, as many women do, and she enjoys occasionally watching a game on television or even attending a game in person. Since women make up nearly half the audiences at professional ballparks, this is hardly unusual or even masculine behavior. When Rachel encounters a man who thinks “it’s not feminine to be such a baseball nut,” she points out that with a lot of men she knows, she can talk to them only about baseball. She hints that this gives her an advantage, a topic they can both relate to.

Moreover, in a careful reading of the novel, I find no evidence that Rachel showed a “desire to continue playing baseball while transitioning into adulthood” and that because she could not do so a “feeling of loss” followed her into adulthood, or that baseball became the vehicle for her to seek liberation from her marriage. Instead, I found that Rachel becomes increasingly determined to cut herself off from the activities she is expected to promote as a rabbi’s wife and goes so far as to take a room downtown to use as a studio where she can pursue her art more intensively. So Rachel uses not baseball but her art as a way to become liberated from what might have become a smothering marriage if she had allowed it to do so.

I believe the author clearly presents baseball as a minor factor in Rachel’s pursuit of independence. The protagonist holds tightly to her artistic skill and celebrates when her persistence pays off and she is finally offered a show of her work. Preparing for it, she works harder than ever, and when she examines the finished work, exclaims aloud, “I am a painter!” The author adds that Rachel forgot about her problems with her husband because, “She had returned to her own world, the only world that mattered. Here, the control was all hers. There was no way another hand could ruin it.” When her husband phones to ask, “Aren’t you coming home?” she replies, “I hadn’t thought about it.”

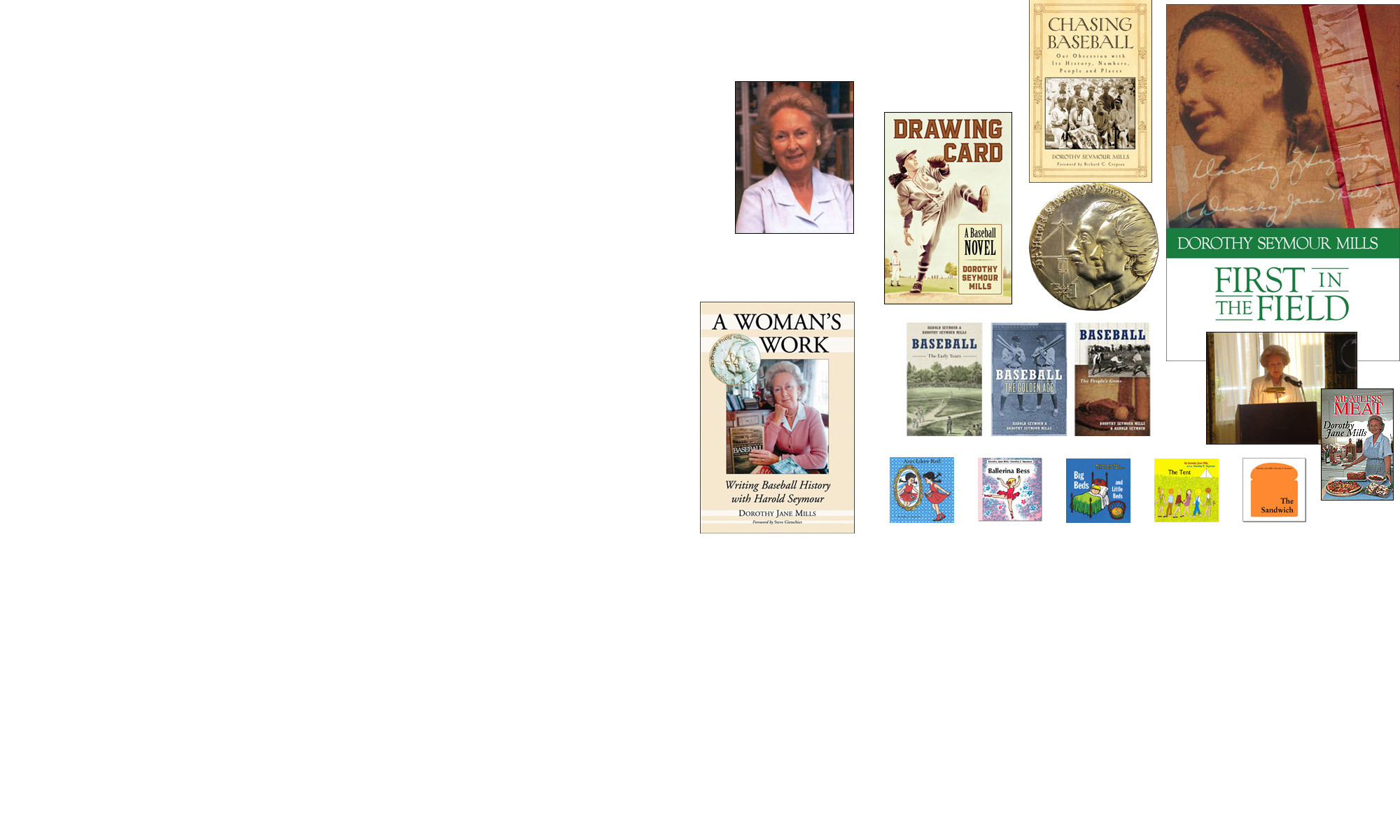

Rachel, the Rabbi’s Wife, is a good read, but it isn’t a baseball novel. The National Pastime plays a minor role in the story, and the heroine is no jock. My own historical novel, Drawing Card, is a real baseball novel. It features a woman named Annie who plays semipro baseball in the days when big cities like Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, and New York were full of women’s teams – the 1930s. She and her teammates love to play and hope to get hired for the minor leagues – as a few women players in the 30s actually were.

But what happened to those few real women players happens to Annie: the contract she signs to play minor league ball is cancelled by Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis as soon as he learns she is a woman.

What Annie does about this and the trouble her actions cause show what can happen when a woman ballplayer keeps her anger warm within her. Anger, it should be said, has no gender. It is neither feminine nor masculine, but it can be deadly.