Last week, while vacationing in New Orleans, I attended a play at the Shadowbox Theatre. The title was “The Insanity of Mary Girard; A Dream in One Act,” by Lanie Robertson. Mary was a real person, the wife of a famous entrepreneur and philanthropist of the 1800s, Stephen Girard, who had her admitted to an insane asylum because of her so-called “uncontrollable bouts of rage” or “emotional outbursts.”

The asylum Mary was committed to, in a basement under the Pennsylvania Hospital, contained a “tranquilizer chair” to which Mary was strapped. The chair had a wooden hood that covered her entire head. Incarceration under these conditions would certainly produce symptoms of madness.

Why did Stephen Girard force his wife into this terrible prison? Because he could. Remember, in the early 1800s women were considered the property of their husbands, to be disposed of as the husbands pleased. Remnants of this view still survive, in what the director’s program notes for the play call “men’s continued belief that they have control over a woman’s body.”

Women’s history presents many examples showing men’s assumption of superior knowledge about the women close to them. Some men still believe they know best how women’s lives should be led. Their pronouncements are made, they believe, “For Her Own Good” — which is also the title of a book recording 150 years of male “experts'” advice to women, most of which today sounds ludicrous.

The decision that women could not play baseball was made by men, despite the fact that American girls must have been picking up the game and playing it since at least the 1800s, because college women are recorded as forming teams and enjoying baseball play beginning with the 1860s.

By the time the 1930s arrived, so many women had played the game that teams were developing excellent players, some so good that the managers of minor-league teams coveted them, despite the unspoken rule against hiring females for major- and minor-league teams. Twice minor-league managers succumbed to this desire for good women players and signed them to contracts, but as soon as the baseball commissioner learned that the signees were women, he cancelled their contracts. He knew not only what was best for minor-league baseball but also what was best for women players.

Girls and women continued playing, but when in 1939 men formed Little League, they prevented girls from joining. It took years of legal battles on the part of parents to obtain the right of their daughters to join Little League teams, where they often had to suffer the meanness of coaches and male players — and the male players’ resentful parents.

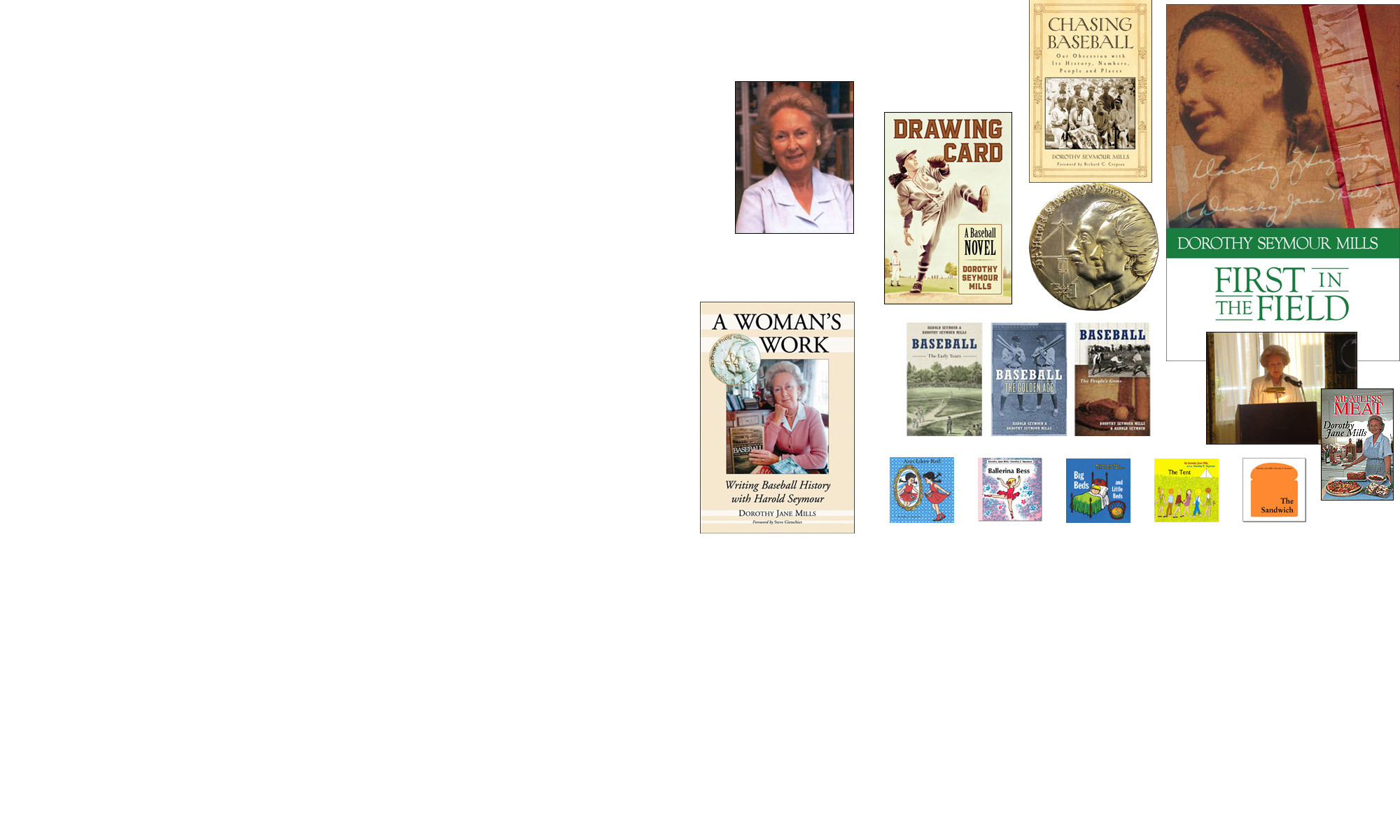

All this makes a dramatic story, one that I am preparing as an electronic book for young people (high school and up), to be published by Thinker Media. Young people deserve to know that women’s baseball, like men’s, has a history, and that it has produced some excellent players, who should have had the chance to participate in the National Game at the highest levels of play.