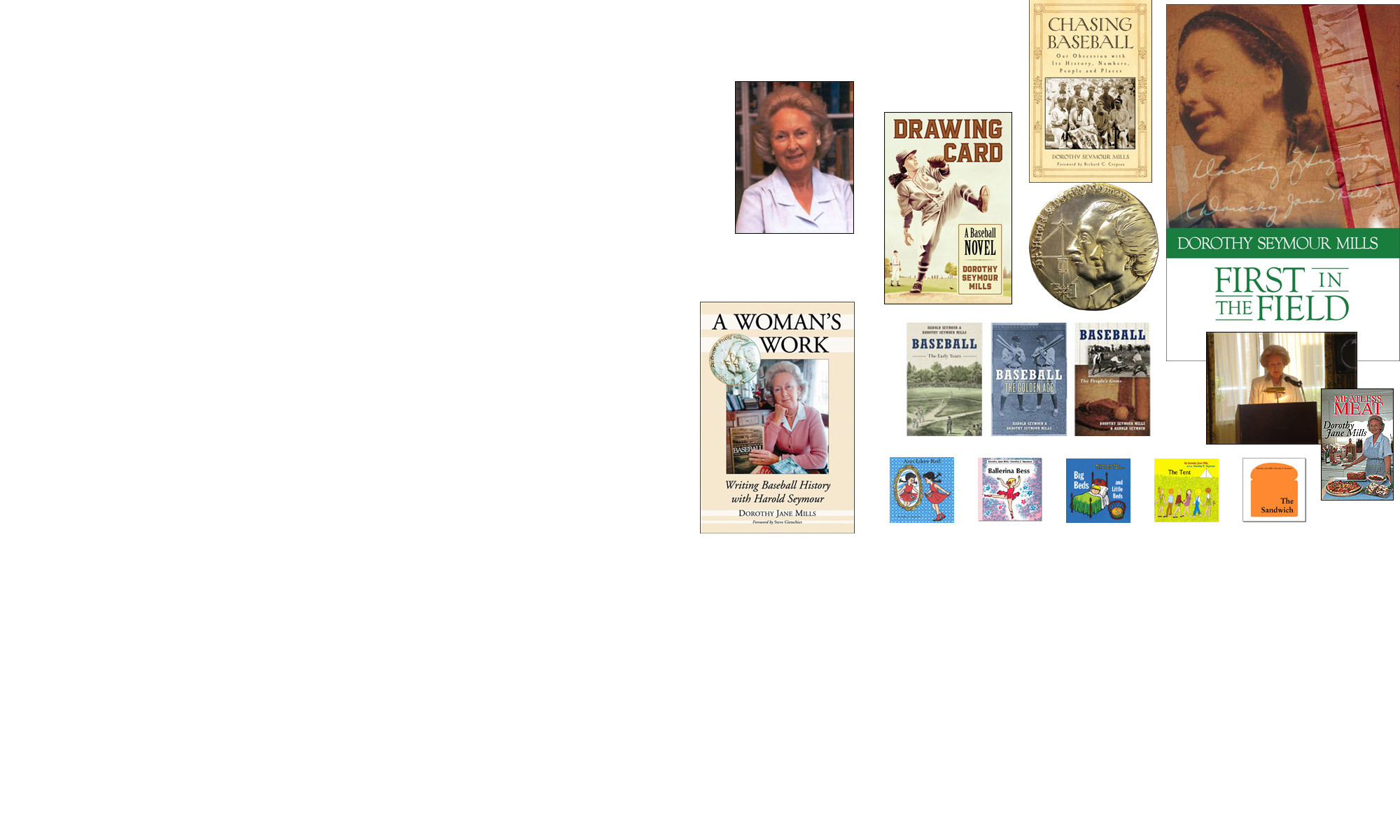

Baseball movies have improved. No longer do they depend on fantasy for effect, like a long-dead ballplayer appearing in the cornfield, or a worn-out player with a magic bat. Happily, now they deal with reality. They feature the type of serious fans I wrote about in Chasing Baseball (McFarland 2010) or the type of women I included in my forthcoming eBook, Who Ever Heard of a Girls’ Baseball Club? Hurrah for that!

In the Drew Barrymore film, “Baseball Fever,” the heroine deals with her attraction to a guy who has for two decades been so obsessed with the Boston Red Sox that he acts really crazy at special events like Opening Day. She eventually has to decide on how much craziness she can put up with for his sake. Luckily, he finally begins to recognize that maybe his fixation has gone overboard.

In a Clint Eastwood vehicle called “Trouble With The Curve,” the daughter of a scout at the end of his career is shown to be more knowledgeable about baseball than most of the men in her life, and she finds a place for herself in baseball, a place where she can make a difference in the building of a successful major-league team.

These plots are believable because, first, today many fans are obsessive fans. They want to go to spring training games in Florida or Arizona, or to visit ballparks all over the country; they can’t miss any important games in which their heroes are participating; they follow the team of their choice and speak of it as their own: “we won,” “we lost,” “we will be playing the Yankees,” “we don’t have a chance against them.” Moreover, their personal lives are full of reminders of their obsession: bobbleheads, uniform jackets, and baseball towels fill their homes, and fantasy league pursuits fill their spare moments.

None of this is necessarily bad, as long as those dedicated to “their” teams realize what they are doing and have a life outside their obsession. They need to keep in mind that besides having a good time, they are doing what a big corporation desires: guaranteeing that corporation a good income for years to come.

Second, plots also become believable when they deal with something new that is happening with women in our country: women are increasingly part of the major-league corporate structure, because men are beginning to understand that some women are not only well-informed about baseball, they have abilities that can be used by major- and minor-league clubs.

While I watched “Trouble With The Curve,” I thought of Katie Haas. She’s an example of a woman who has made a place for herself in baseball. Katie Haas has worked for 18 years with the Boston Red Sox. She was selected by the club to supervise the building and operating of the club’s new spring training park in Fort Myers, Florida.

To handle this job, Katie moved with her family from Boston to Fort Myers, and she worked with the (male) contractors whose companies constructed the whole facility under her supervision. The stadium and practice fields were finished in time for the club’s spring baseball training visit.

Although Katie had never worked in construction, she found that she could manage the job.

“I listened and learned,” she explained. “I have brothers, and I was always a tomboy.”

After spring training, Katie, who has a college degree in marketing, worked to find other events that she could hold in the stadium, so that it would continue to bring in money for the club. She also found a lot of ways to help the important charities in Fort Myers.

Katie has made herself part of the community in Fort Myers. Her husband, a scout for the Orioles, is away a lot, looking for players. Katie also has a daughter of preschool age. It wasn’t easy to supervise the building of the ballpark and grounds while raising her little daughter, but many women in every kind of work face this problem today if they want to have both a career and a family.

So enough with the supernatural appearance in cornfields of long-dead players and with the unlikely success of a worn-out player with a magic bat. Reality is a lot more interesting.