By Gene Carney

By Gene Carney

“It ain’t braggin’ if you can do it.”

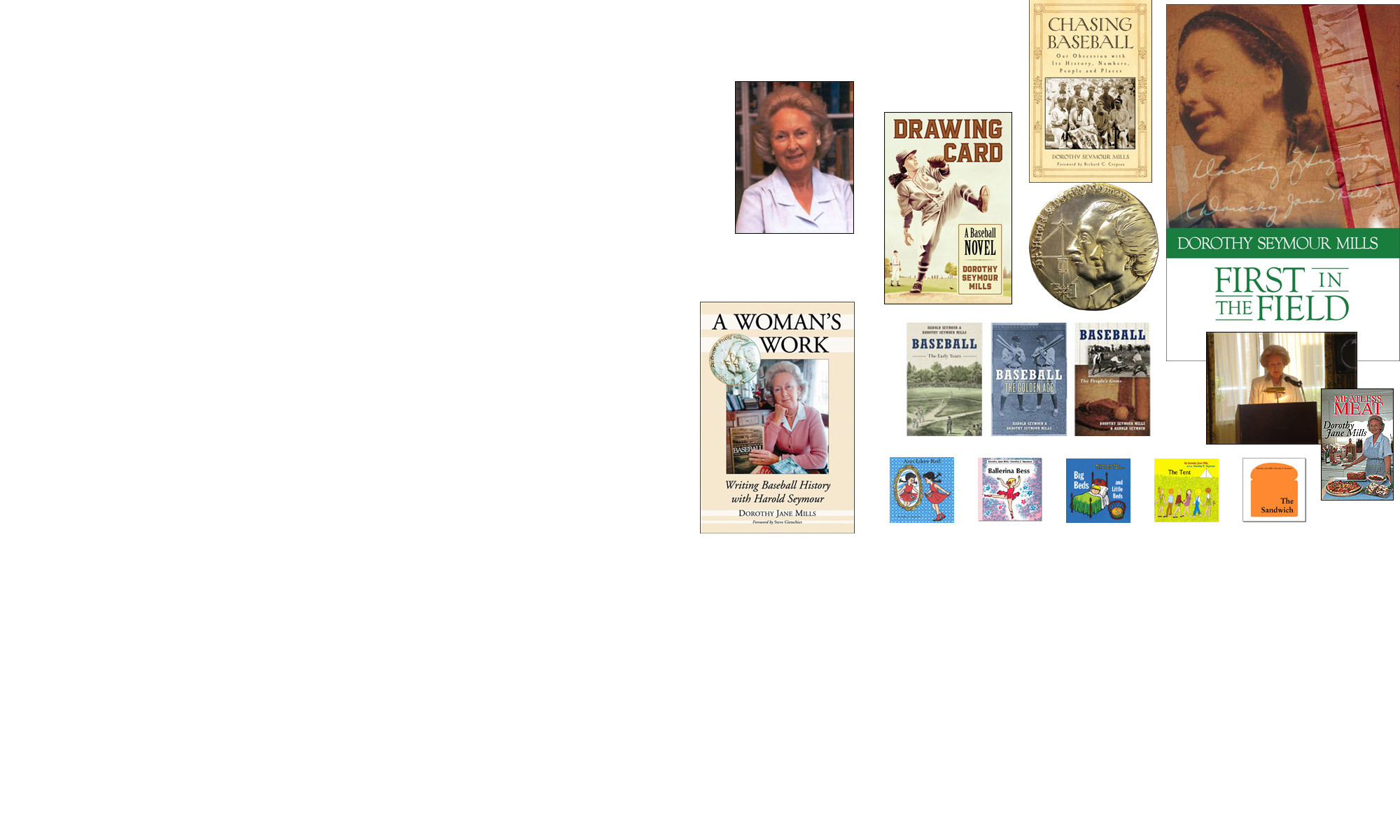

That old Dizzy Dean saying came to mind as I finished reading A Woman’s Work: Writing Baseball History with Harold Seymour, by Dorothy Jane Mills (McFarland, 2004). It’s a brisk and remarkable read; usually when I enjoy a book I recommend it, but after this one, I find myself wanting to recommend the small library that Dorothy Mills has brought into the world herself, along with those volumes that bear the name of her late husband.

Another saying came to mind, too: Give credit where credit is due. That seems like an easy maxim to follow, but in my experience, it can be harder than hell to pull off. Many of the pages of A Woman’s Work are tinged with mixed emotions, as Dorothy describes her role in the researching, editing and writing of what went down in history (almost) as the Harold Seymour Baseball History Trilogy. Dorothy makes it clear that she deserved more credit all along the way, and her claiming it decisively in recent years seems only fitting.

I should state up front that I received a review copy, which happily was not a factor in my evaluation of the book. That I met Dorothy Mills nearly six years ago, and have kept in touch, was.

Back in May 1999, I attended the Seymour Conference in Cleveland, Ohio (you can look it up, in Notes #189). I knew Bruce Markusen, that year’s Seymour Medalist, but I did not attend only to celebrate with Bruce. I had not been to Cleveland for 22 years, having lived and taught high school in that city between 1968-1974. I remember the weekend as much for reunions with old friends as for the conference. I wound up on a panel with Mike Shannon and perhaps others, at the tail end of the event, and just as it was over, I ran into Dorothy Mills.

In A Woman’s Work, Dorothy states her unequivocal preference for writing historical fiction, versus history.

More than that, I like to write in other forms: essays, recipes, news releases, humorous articles, poetry, scholarly writing, travel pieces, letters, children’s stories, editorial reports … whatever seems required in order to express the idea or purpose I have in mind.

I had been writing baseball just ten years (Dorothy had a four-decade head start on me), but she seemed, in our brief encounter, a kind of kindred spirit. She convinced me in a few minutes to take a serious look at publishing via the internet.

I must have mentioned that I had written a play that was historically based. I was delighted when she expressed an interest in reading it — I was anxious to find any “problems” that a baseball historian would spot. Mornings After, which revolves around an obscure Hall of Fame pitcher, Addie Joss, plainly did not grab Dorothy, although at least the history stood up to her scrutiny. But when I mentioned that I had written lyrics, she immediately brightened up and put me in touch with Lowell Kammer (of Niagara Falls), with whom I collaborated to turn Mornings into a musical.

A theme in A Woman’s Work is Dorothy’s amazing memory, and her gift for networking. If Harold Seymour seemed unable to give credit where it was due, Dorothy seems to never have had that problem, and her book is filled with the names of countless people who assisted her over five decades and counting, in ways large, small, or strange. Clearly, she knows the joys, and the advantages, of keeping in touch.

Last June, I spent a day at Cornell University with the Harold and Dorothy Seymour Collection. The full story is in Notes #297, but here is an excerpt:

I think the greatest discovery I made had nothing at all to do with the thousands of note cards and folders I sifted through. That was fun, but what was really exciting was realizing I was getting inside the minds (Harold did not work alone) of true historians. There were no copiers back then, people took notes by hand, pencil or pen on paper, the way Medieval scribes copied manuscripts, the way we all learned to write. It was primitive and inexact, and it added another layer to be deciphered — what is that word? But handwriting reveals, too, and notes jotted in blue or green might be accompanied by notes in red that asked questions, or made comments, or evaluated the text copied. Exclamation points and stars were scattered about — these texts deserved special attention. Why?

If I thought I was inside the Seymours’ minds then, it was nothing like the guided tour Dorothy provides in A Woman’s Work. In a sense, the book is like one of those The Making Of programs that often follow films. Done well, these can be more educational and entertaining than the movie itself. In the case of A Woman’s Work, learning how the Seymour histories came to be written is fascinating, but it also whets the appetite. I’m extremely familiar with the several chapters on the 1919 World Series fix in Baseball: The Golden Age; but now I have a sense of what I’ve missed by not reading the whole trilogy. Mea culpa.

For all A Woman’s Work reveals, it also conceals much, and that’s not such a bad thing. We see Dorothy and Harold as co-researchers, editors and authors, but rarely as husband and wife. And that’s OK, although I suspect some readers will be disappointed at that. Harold apparently wrestled with depression much of their time together, and later Alzheimer’s, at the end. The first line of my poem Boxscore is “Chadwick’s love child” — and by the end of Dorothy’s book, I was viewing the books they produced together as their “children” — an image Dorothy does not use herself, perhaps because the contributions of the parents were never equal, especially for The People’s Game.

A Woman’s Work is more than its subtitle suggests, although writing baseball history — as pioneers, no less — is the center of the book. Happily, it also is very autobiographical, as Dorothy tells of her many and varied other interests. These are almost too many to list, but they are so impressive that readers cannot wonder what this woman might have done had she not latched onto baseball, Harold’s focus. As a baseball fan, I’m delighted that she did, but I still have to wonder. But we all wonder about choices we made at different points in our life.

Marriage is much in the news these days. For better and for worse, richer or poorer, in sickness and in health. Marriages are all different. Dorothy and Harold’s is surely more unique than most. What if I had married a baseball nut? But I didn’t; Dorothy did. And her story is worth the telling, and worth the reading.

This review by Gene “Two Finger” Carney appeared in Notes from the Shadows of Cooperstown, an eclectic and ecumenical publication of anything and everything baseball.

Carney is the author of Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-Up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded, Romancing the Horsehide: Baseball Poems on Players and the Game and the historically-based baseball play Mornings After, as well as numerous short stories. Carney passed away in 2009.