What follows is a copy of an article written by Professor George Grella about the 1995 ceremony at Doubleday Field, Cooperstown, New York, during which the ashes of Dr. Harold Seymour, the historian of baseball and my first husband, were sprinkled around first base.

Harold Seymour (1910-1992)

by George Grella

On clear nights in the tranquil hamlet of Cooperstown, capital city of our dreams, the sky seems close and palpable, a black velvet canopy decorated with thousands of stars the perfect foil for a special diamond, just the right background for the contemplation of eternity. In the cool darkness of such an evening in early June of 1995, an assortment of fans, at least enough to staff a couple of teams, gathered in Doubleday Field to attend not a baseball game but a kind of funeral, a burial and memorial service for a man who had devoted most of his life to the study of the game. Mostly academics from a variety of disciplines, they assembled in the grandstand above the darkened field along the first base line to remember the life and work of the baseball historian Harold Seymour and to witness and participate in the scattering of his ashes on the field itself. Although the occasion an the ceremony may seem strange or even comical, as they did initially to a few of the company, they turned out to be sweetly appropriate, somewhat lighthearted, and yet oddly touching, not at all a bad way to bid farewell to a distinguished scholar of the great American game.

The small crowd might properly deserve the oxymoron of professional amateurs, serious scholars of the game who also live it with the intensity that no other sport and few human endeavors can evoke. Coming mostly from universities and colleges all over the country, they had assembled in Cooperstown for the Seventh Annual Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, at which they spent a considerable amount of time delivering, listening to, and discussing papers on any number of relevant subjects, including the history, literature, cinema, art, aesthetics, and philosophy of baseball (Seymour himself had addressed the gathering in a keynote speech in 1990). They attended dramatic readings of baseball poetry and prose, and earlier in the evening they even played their annual game of Town Ball, a direct and immediate ancestor of the modern game. Not only as scholars but simply as enthusiasts they did what all fans do: they talked baseball, perhaps the best talk of all, providing an all-too-uncommon version of what intellectual discussion should be, a discourse lively and literate, passionate and profound, grounded on both love and knowledge.

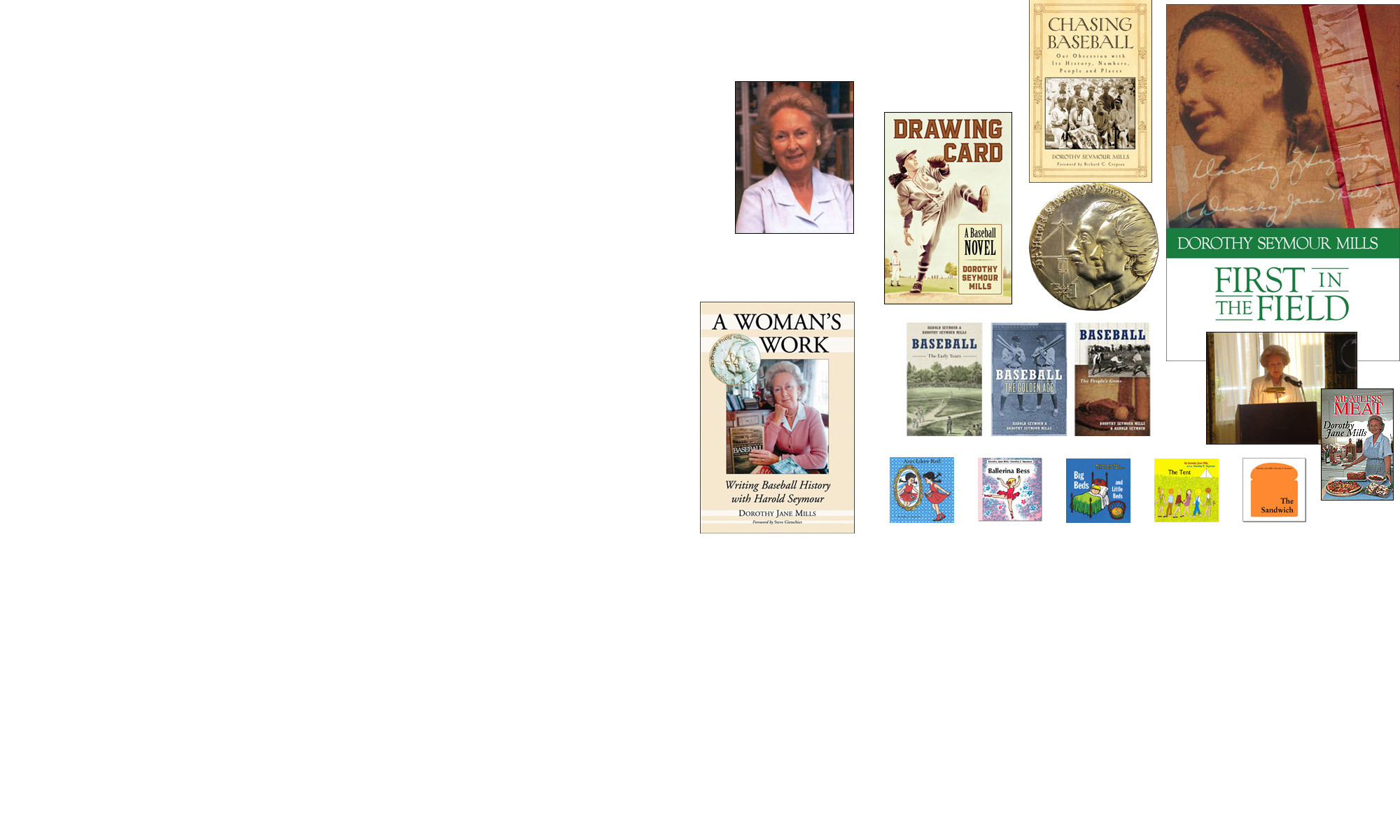

Alvin Hall, dean of continuing education at the State University of New York at Oneonta, the genial, loquacious host and energetic organizer of the Symposium, presided over the occasion. Tom Heitz, former director of the Baseball Library and Archives at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, read a eulogy that Seymour’s widow Dorothy, also in attendance, had helped prepare; he touched on the several major aspects of Harold Seymour’s long and rewarding career in baseball, as player and coach, teacher and student, and above all, as the ground-breaking historian of the game. Others read excerpts from some of Seymour’s best-known and most representative works, including his monumental three-volume history, Baseball: The Early Years (1960), Baseball: The Golden Age (1971), and Baseball: The People’s Game (1990).

Although the occasion, of course, was intended as a solemn final tribute to an important pioneer who blazed the way for innumerable followers, it never sank into the maudlin or the lugubrious. Many of the passages of Seymour’s work examined their subjects in humorous terms, especially those from his reminiscence of his service as a batboy for the Brooklyn Dodgers in the era of the colorful Wilbert Robinson, where the young man advanced his knowledge of two languages, “English and profanity.” In Baseball: The Golden Age he wrote about the tendency of players of the past to contract venereal diseases, which the newspapers reported as “malaria.” (America must have been a swampy, mosquito-ridden place in the early part of the century to allow those stories to fly; in recent years the “pulled groin muscle” has served a similar purpose.)

The readings also helped remind the crowd of the importance of Harold Seymour’s achievements to the serious study of the game and therefore to those attending the Symposium. In the face of considerable opposition and even scorn from his department at Cornell, he wrote the first doctoral dissertation on baseball, the longest ever submitted at the university, which formed the basis for his magnum opus. Unlike the previous histories, his works proceeded from a thorough grounding in basic research, a meticulous regard for fact, and a refreshingly disinterested point of view; he did not, like many previous chroniclers, stridently propagandize for the sport or employ it as an excuse to promote some narrow notion of nationalism. He discussed some of the actual history of the game, helping to lay to rest the apocryphal story, probably never more than half-believed, of Abner Doubleday’s invention of the game there in Cooperstown in 1839.

Most students of the sport and of Seymour’s valuable work probably expected that the third volume of his study would follow sequentially from the first two, dealing with the game up to a point somewhere near the present time, perhaps bringing it into its second Golden Age in the 1950s. Instead, he wrote the aptly entitled Baseball: The People’s Game, devoted to a rich and important chapter of baseball’s crowded history, neglected by many scholars, the game as it was conducted outside the confines of Organized Baseball (his capitals).

In that volume he covers its endless incarnations in informal local contests in village greens, sandlots, and cow pastures, the various levels of amateur ball, its emergence as a college sport (including at women’s colleges), baseball in the military, the beginnings of black baseball, and so on. That necessary book reminds us all that the best, the most authentic baseball takes place not in the sterile confines of some concrete tureen that owners call a stadium but in other venues far from the major leagues. Out there, all over America, it is truly the people’s game as the people actually play it.

Despite the relative informality of the presentations and the resolutely secular nature of the ceremonies, the occasion, like so much of baseball, also hinted at the spiritual and the transcendent. Directly down the leftfield foul line, just beyond the outfield fence, a single light glowed in a church steeple, like some combination of Magritte and Norman Rockwell, underlining the vital connection between traditional religion and what Annie Savoy in Bull Durham calls “the church of baseball.” We all know that ball parks are temples, holy places that combine the exuberant activities of sport and faith. The dark and empty field, further, was haunted by innumerable ghosts: the spirits of all those thousands who had played this beautiful game in this lovely place. It was even haunted specifically by those individuals, many of them Hall of Famers, players, owners, managers, and umpires, whose own remains had mingled with the mythic dust of that magical ball park. Now and then a trick of the dim light or a flicker of some fan’s imagination coalesced around the image of some spectral figure patrolling the outfield or running the bases. Sitting in its dark bowl of stars, the stadium was peopled, moreover, by the millions more who loved the game and, correctly or not, regarded Doubleday Field as a site of special sanctity. No wonder Kinsella’s protagonist in Shoeless Joe says that “a ballpark at night is more like a church than a church.”

The simple fact of that location itself suggested some complex ironies. Although Harold Seymour had quite rightly rejected the mythology of Abner Doubleday’s “creation” of the game, he also chose to have his ashes scattered at the purely imaginary location of that entirely fictitious occurrence. Some special wonder attaches to that choice of so completely mythical a spot, as if even to a historian the myth itself were more important than the historical fact . . . and, of course, it is. Doubleday Field is obviously the real field of dreams, or perhaps the dream field of reality, a truer place than any actual one, an enchanted spot in a magical village, the nation’s home plate, the universal home town of the American imagination. It’s the only proper place for a passionate fan and distinguished scholar of the game to repose.

After the readings and a gracious response from Seymour’s widow, Dorothy, the crowd filed out of the grandstand and assembled near first base, the position Seymour himself had played as a youth. There an admirer, Chris Jennison, himself a baseball writer, scattered the ashes on the base path, where they would mix with the sacred earth of the field and with the remains of those who had preceded him: Doubleday Field is hallowed ground, indeed. The group then sang, what else? “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” For the first time, what had always sounded like a carefree, exuberant invitation became something of a hymn, even something of a dirge, a sad song not only for Harold Seymour but for all the fans and players of all the games gone by, with perhaps the hint of hope that baseball really is forever, that they really do play the game in Heaven. If there’s no baseball in Heaven, then what’s a heaven for?

After the singing, the scattering of the ashes, and perhaps, for some, a few private words to the close and holy darkness, the ceremony ended. By way of benefaction, the jovial Al Hall pronounced the last word. Now, he said, whenever he saw that famous, endlessly repeated, endlessly entertaining Abbot and Costello routine, he would always know who’s on first. Anyone who goes to Cooperstown with the proper pilgrim attitude, as a devout Catholic would visit Rome or a Muslim journey to Mecca, should stop off in Doubleday Field and remember all those who play there in spirit; the visitor should also cast a glance toward first base and think for a moment of a player from the past who figured so importantly in the study of the game, remembering who’s on first, remembering Harold Seymour.

George Grella is a professor of English and film studies at the University of Rochester who has published extensively on baseball.